In our previous article, we discussed how to identify when you have a range advantage or a nut advantage in a given spot. In this post, we’ll go a step further and break down additional concepts that are essential for understanding poker ranges at a deeper level.

Once you spend some time studying GTO strategies, you’ll notice that ranges tend to organize themselves in consistent, structured ways depending on the situation. There are specific terms that help describe these patterns more clearly - and understanding them can significantly improve how you approach hands at the table.

What Is a Linear Range in Poker?

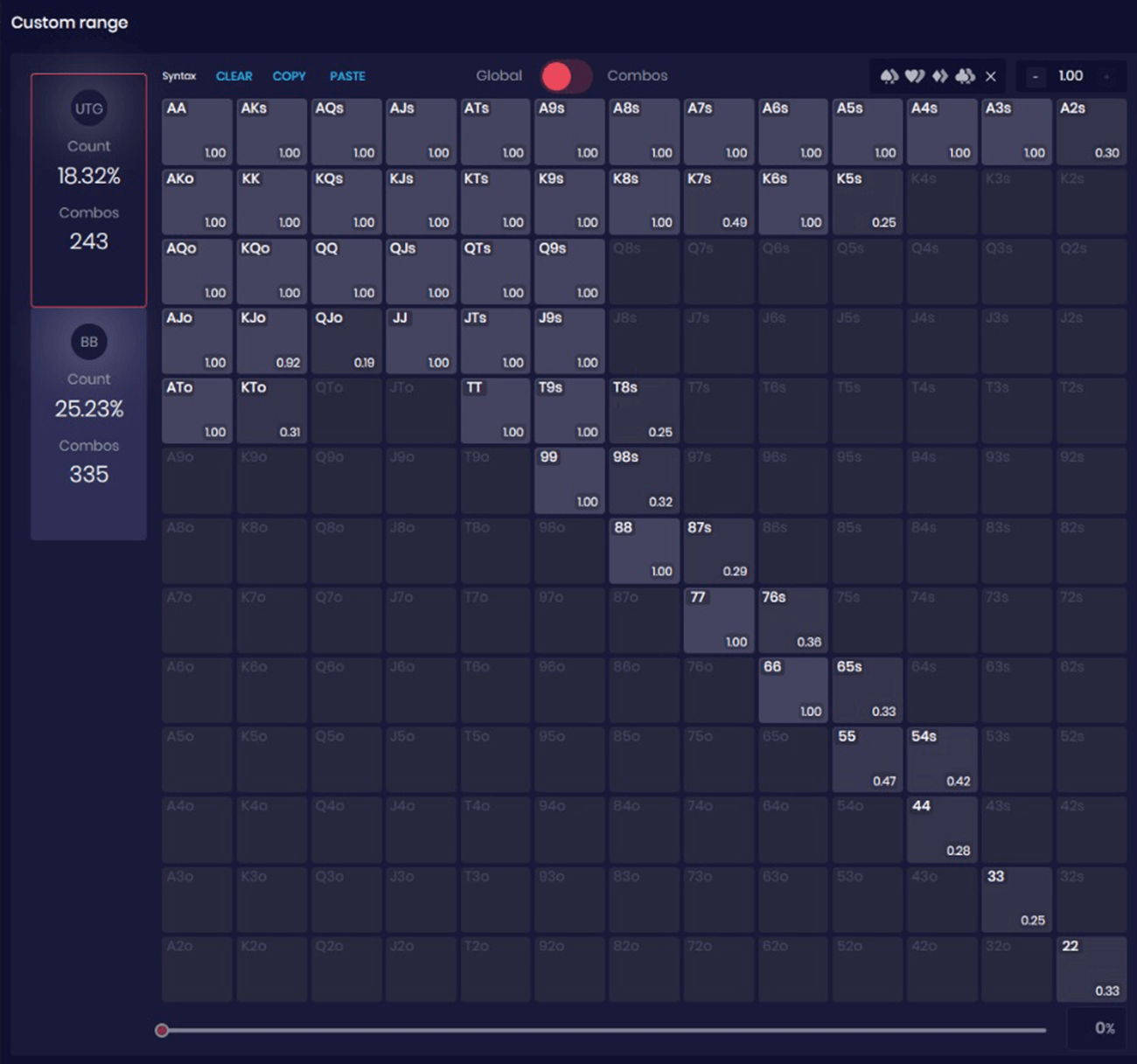

A linear range in poker includes the strongest and most playable hands in a continuous, top-down fashion. One of the clearest examples is a first-in opening range.

Let’s say you’re playing a standard 100 BB cash game and you're first to act Under the Gun against unknown opponents. In this spot, you’re likely opening around 18% of hands. This range includes the strongest and most straightforwardly playable hands - premium pairs, strong broadway hands, and suited connectors. Since the selection is based on raw hand strength from the top down, this is referred to as a linear range.

A similar concept applies when the action folds to the Big Blind, who faces an open raise. The BB defense range is also often linear, but typically shifted: it excludes the absolute strongest hands (which would have 3-bet) and the weakest hands (which are folded), and instead includes a middle slice of hands that are playable but not strong enough to raise. Again, this results in a linear cut - just from a different part of the overall hand spectrum.

In tournament poker, a common linear range appears when the Big Blind is facing a shove from the Small Blind. The Big Blind will call with a specific percentage of the strongest hands, depending on stack sizes, ICM pressure, and player tendencies. While the exact percentage varies, the structure is the same: it's a top-down slice of the strongest hands, making it a textbook example of a linear calling range.

Now contrast that with a polarized range, which follows a very different logic.

Polarized Ranges in Poker

A polarized range consists of two distinct groups of hands:

- Nutted hands – those that beat almost everything in your opponent’s range.

- Bluffs or trash hands – those that are too weak to win at showdown and are often beaten by your opponent’s entire range.

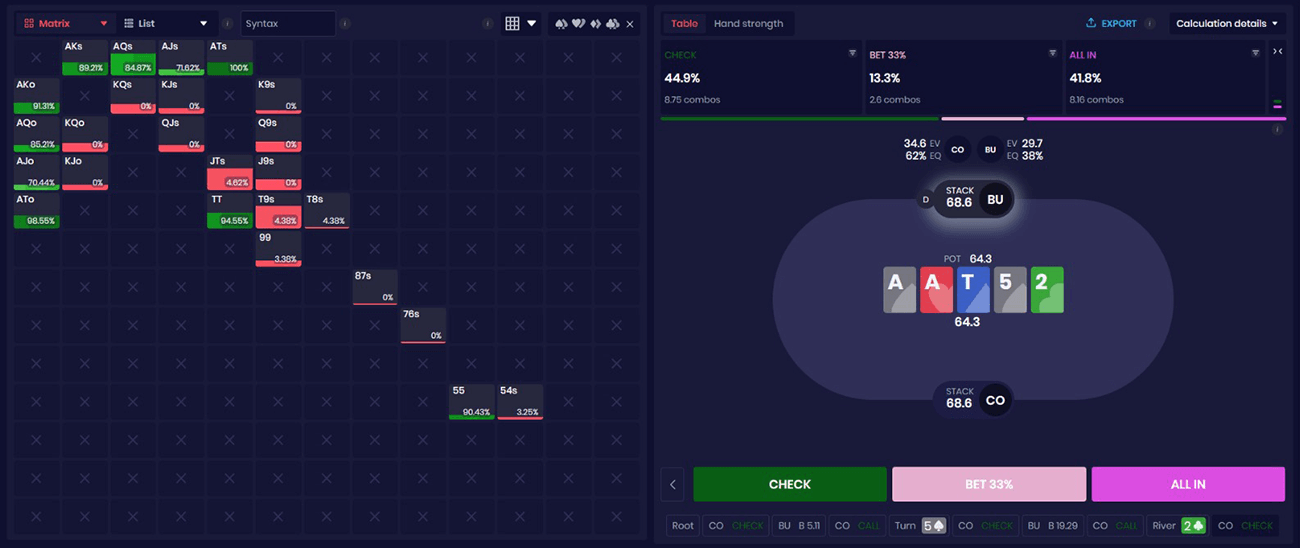

Let’s say you're on the Button, you 3-bet versus a Cutoff open, and they call. The board runs out A♠ A♦ T♣ 5♣ 2♥. You’ve c-bet the flop and barreled the turn, and now you’re on the river.

At this point, your possible holdings tend to fall into two categories:

- Very strong hands (e.g., trips, full houses) with 70%+ equity.

- Complete air (missed bluffs) with almost no showdown value.

In this spot, your river betting range should be polarized:

- Value bets come from the top of your range.

- Bluffs come from the bottom - hands with no showdown value that can fold out better hands.

You don’t want to bet medium-strength hands here, as they rarely get called by worse and rarely fold out better.

While most preflop ranges are linear, polarized ones do occur in some spots - though less frequently. A common example is raising from the Big Blind versus a Small Blind limp in tournament poker.

In this scenario, the Big Blind often raises:

- Premium hands (e.g., AKo, QQ+, suited broadways) that are happy to play for stacks.

- Very weak hands (e.g., offsuit 2x, 3x, 4x) that have poor playability postflop but can occasionally take down the pot preflop.

Hands in the middle (like Q8o, K7o, small suited connectors) are often just checked, because they aren’t strong enough to raise for value, nor weak enough to justify using as a bluff.

Situations involving these kinds of hands often lead to what’s known as a condensed range.

What Is a Condensed Range in Poker?

A condensed range is the opposite of a polarized one. Instead of having extremes (nut hands and bluffs), it’s made up mostly of medium-strength hands. A condensed range lacks both the very best and the very worst holdings. This “condensation” occurs because the player using this range is capping their holdings—removing premiums and folding the weakest hands.

One of the most common examples of a condensed range is when the Small Blind flats a raise in tournament poker.

Let’s say you're in the Cutoff with 40BB and open-raise. The Small Blind, holding a similar stack, chooses to call instead of 3-bet. In this spot, their flatting range is highly condensed:

- They usually exclude the strongest hands (those would be 3-bets).

- They also fold the weakest holdings (too weak to call profitably out of position).

As a result, their range is made up of suited broadways, medium pairs, suited Aces, and playable suited connectors - hands that perform decently postflop but aren't strong enough to raise or weak enough to fold.

Strategic implications for c-betting

Even though you’ll still often hold a range and nut advantage as the preflop raiser, your c-bet strategy against a condensed Small Blind calling range should differ from your strategy versus the Big Blind.

Against the Big Blind, who defends with a wide and often unstructured range, many boards allow you to c-bet aggressively - there are plenty of combos that completely miss and fold immediately.

But against the Small Blind, it's a different dynamic:

- Their range is tighter and more connected to the board.

- Even without the nuts, they’ll hit many flops with decent equity.As a result, your c-bets face more resistance, and over-bluffing becomes more punishable.

While condensed ranges are centered around medium-strength holdings, there are also spots where the range includes a broader mix of hand strengths - that’s where merged ranges come in.

What Is a Merged Range in Poker?

A merged range includes a balanced mix of:

- nut hands (top of range),

- buffs (bottom),

- and medium-strength hands (the in-between).

Unlike polarized ranges, which only include extremes, a merged range gives you more flexibility on future streets. This makes it particularly well-suited for spots like check-raising on the flop, where you want to retain strong hands, apply pressure, and stay balanced across many turn and river runouts.

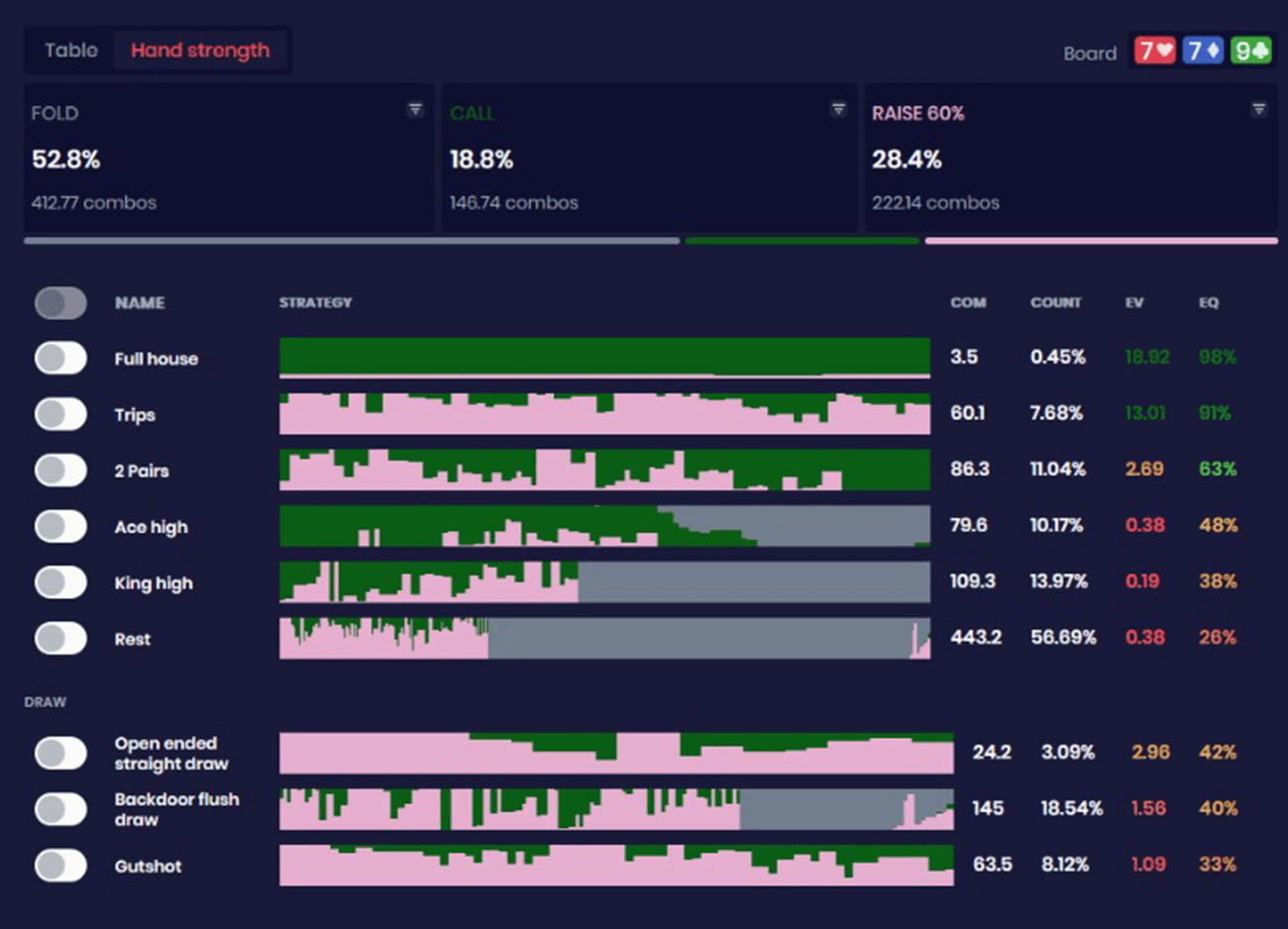

Consider a Button vs Big Blind situation at 40BB stacks. The Button open-raises, and the Big Blind defends. The flop comes 9♠ 7♦ 7♣ rainbow.

When the Button c-bets, solvers suggest that:

- The Big Blind should respond with frequent aggression, often check-raising.

- Importantly, this check-raising range is merged - it’s not just full houses and bluffs.

If you study the solver output, you’ll see that the BB is supposed to raise a bit of every hand category:

- some 9x and 7x for value

- some 8x, 6x, and random overcards as semi-bluffs

- occasionally, even underpairs or backdoor-heavy hands.

This leads to a resilient, flexible range on the turn:

- you can improve to showdown value by pairing up.

- you can continue betting for value with strong hands.

- you can keep bluffing on suitable runouts.

Had you constructed your range in a polarized way - only with trips or air - you’d lack this flexibility. Your turn options would be more binary: keep blasting or give up.

Learn to Recognize Who Is Capped

One of the most essential concepts in working with poker ranges is understanding who is capped and who is uncapped.

A capped range lacks the strongest possible hands on a given board. For example, when the Big Blind defends versus an early position raise, they usually don't have hands like AA, KK, or AK - so on a board like A♣ K♦ 8♠, they are structurally capped. They simply don't have the top sets or top two-pair combos that the preflop raiser can have.

The opposite can also be true. On a low-connected board like 9♦ 8♠ 6♥, the early position player is now capped, because their range lacks suited connectors and low pairs that the Big Blind can easily have. The Big Blind, in that case, is uncapped and can credibly represent the nuts.

An uncapped range includes all of the strongest hand combinations possible given the board texture. But ranges can shift. A player who was uncapped on the flop might become capped later - like when the board pairs on the turn or river and only one range realistically contains trips or full houses.

Understanding who is capped heavily influences strategy.

The uncapped player typically takes the aggressive line, by betting big, applying pressure and realizing more equity across their range.

With tools like poker solvers, identifying capped and uncapped spots has become more accessible than ever. The key is applying that understanding in real time - so you can recognize when your opponent is structurally limited and capitalize on it.